(Max Frenzel) I tried a ten-week program of resonance breathing to see if it would make a measurable impact on my anxiety. With the combination of hard data and more subjective analysis of the results, I would go as far as to say that the sense of anxiety I experienced last year is now completely gone again, and that the resonance breathing practice played a role in this.

Related Wim Hof Teaches Mikhaila and Jordan Peterson His Breathing Method (Video)

by Max Frenzel, February 9th, 2021

2020 was a stressful and anxious year for many of us, and I’m certainly no exception to this.

Besides the pandemic, I also published a book, which at times made me feel like a hypocrite when I didn’t completely live up to my own writing, started to finally address my commitment and intimacy issues (for lack of a better simple description), and changed jobs. The combination of these and other factors made me, for the first time in my adult life, experience something I’d describe as anxiety.

I wouldn’t label it as anything close to “severe” or “crippling” anxiety, but it was a clear contrast to how I usually felt, and it definitely had a negative impact on my mental health, my relationships, and my performance.

But I’ve always believed in self-improvement, and never accepted that “this is just how things are.” So naturally, I set out in search of a solution.

Besides starting to work with a coach and a counselor (which I can really recommend to EVERYONE, despite the unfortunate stigma around it — I use Coach.me and betterhelp.com respectively), the one thing that helped me most was the simple act of breathing.

Breathing, in a very deliberate way.

Breath — The Universal Life Force

Breathing is one of the most fundamental things we do.

Despite — or maybe because of — its critical importance, we don’t have to put any conscious thought into it. As part of our autonomic nervous system (ANS), which also controls things like heart rate and blood pressure, breathing is a mostly passive process. As a result, most of us spend very little time thinking about our breathing.

However, just because it happens by itself, doesn’t mean we are breathing in an optimal way. Nor does it mean that we cannot consciously control the process to achieve some desired result if we set our mind to it.

“We assume, at our peril, that breathing is a passive action, just something we do. […] But breathing is not binary.”

— James Nestor

In fact, many of our ancestors were much more aware of their breath than we are today.

As James Nestor points out in his excellent book Breath, the ancient Indus Valley civilization is not known to have worshipped any gods or practiced any religion — no religious depictions have ever been found. But what has been found are depictions of people breathing consciously. And the Indus Valley people are no exception in their worship-like focus on breathing.

Almost all ancient civilizations — from Asia to Europe, Africa, and the Americas — had a concept of “life force,” what Indians called prana, chi in Chinese, or ki in Japanese. And this life force was almost synonymous with breath.

Even though much of this ancient wisdom has been largely forgotten by the average population today, there are still many active practitioners of conscious breathing.

By controlling their breathing, many advanced yogis can do seemingly impossible things like control their body temperature, blood flow, and even control, or stop, their heart itself. The effects are scientifically well documented even though the mechanisms are not fully understood yet.

While I’m nowhere close to the experience or control of such outliers, I was also not a complete stranger to conscious breathing myself.

Tummo, or Inner Fire, is a breathing technique developed and practiced by Tibetan monks, and it has recently been “modernized” and popularized by the Dutchman Wim Hof, also known as The Iceman for his many feats and records relating to cold exposure.

Like a growing number of people, I experimented with the Wim Hof Method, which to oversimplify a bit, is essentially controlled hyperventilation (combined with cold exposure).

Around 2015 I practiced daily for several months, and have since been doing it on and off, or whenever I felt like it. It’s got an increasing body of research backing its efficacy, and I generally perceived a boost in energy and focus after practicing.

But the Wim Hof Method is far from the only breathing technique that has gotten a modern overhaul and gained support from the scientific community.

To address my growing stress and anxiety in 2020, I decided to give a technique known as Resonance Frequency Breathing a go.

HRV and Resonance

I first came across resonance breathing through Tim Ferriss.

In a podcast episode in which he revealed his struggle with childhood trauma, he mentioned that HRV biofeedback training was one of the tools that helped him most on his healing journey.

HRV, or heart rate variability, is a metric I have been interested in for a long time. It captures how much the time interval between consecutive heartbeats varies.

Somewhat counterintuitively, the more variation, the better.

A heart that beats like clockwork with no variation between beats is a sign that our body is stressed.

If we are relaxed and well-rested, on the other hand, our heart can adapt to minute changes in our environment, constantly fine-tuning the heart rate to the demands of the current moment.

Because of this, HRV has become one of the key markers of mood, stress adaptation, performance, and even overall health.

I recently shared the results of tracking my HRV during sleep with my Oura ring for two years, analyzing how different factors (like alcohol, caffeine, and bedtime) impact it.

mentioned above, Tim Ferriss noted that he worked with Dr. Leah Lagos for the HRV training.

Lagos has recently published a book called Heart, Breath, Mind in which she describes her method, wrapped into a ten-week program. This is the program I followed for my own experiment.

While this article is supposed to be self-contained, it is also simplified and shows my own personal adaption and experience. For more details, I have shared my notes on the book on my website, and I also highly recommend picking up the original book.

Our heart is just like any other muscle in that it has a muscle memory that can be trained.

The ten-week program outlined by Lagos in her book aims at exactly this, using our breath to help our heart unlearn bad patterns, ingrained through trauma, anxiety, or just bad breathing habits, and relearn patterns that make our heart more responsive and resilient.

In doing so, we also address the balance between our sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system, which are responsible for fight-or-flight and rest-and-digest respectively.

For many of us, this balance has shifted far too much to the sympathetic side.

As Lagos puts it,

“Most adults have a dominant sympathetic nervous system and an underactive parasympathetic nervous system. […] You’re driving a car that has no trouble reaching a high speed but is incapable of slowing down.”

Through the constant bi-directional dialogue that’s taking place between our heart and our mind, we can train the former to calm the latter, strengthening the parasympathetic nervous system and dampening the response of the sympathetic nervous system.

Finding your resonance frequency

The most common resonance frequency is around six breaths per minute — four seconds inhale and six seconds exhale on each cycle — but according to Lagos it can be as low as four and as high as seven breaths per minute.

Interestingly, James Nestor points out in Breath that almost all traditions in the world contain forms of prayer, chanting, or meditation that, when analyzed, lead to a slow breathing rate of around 5.5 to 6 breaths per minute, which happens to exactly coincide with the typical range of resonance frequencies that modern science has found.

“The resonant breathing offered the same benefit as meditation for people who didn’t want to meditate. […] It offered the healing touch of prayer for people who weren’t religious. […] Prayer heals, especially when it’s practiced at 5.5 breaths a minute.”

If you don’t want to bother specifically getting any new devices for resonance breathing, you can just stick to the average six breaths per minute. Even if it’s not exactly your resonance frequency, you’ll still reap some of the benefits.

But if you really want to practice at your optimal frequency, now is the time to get out the gadgets.

Tracking Breath Pacing

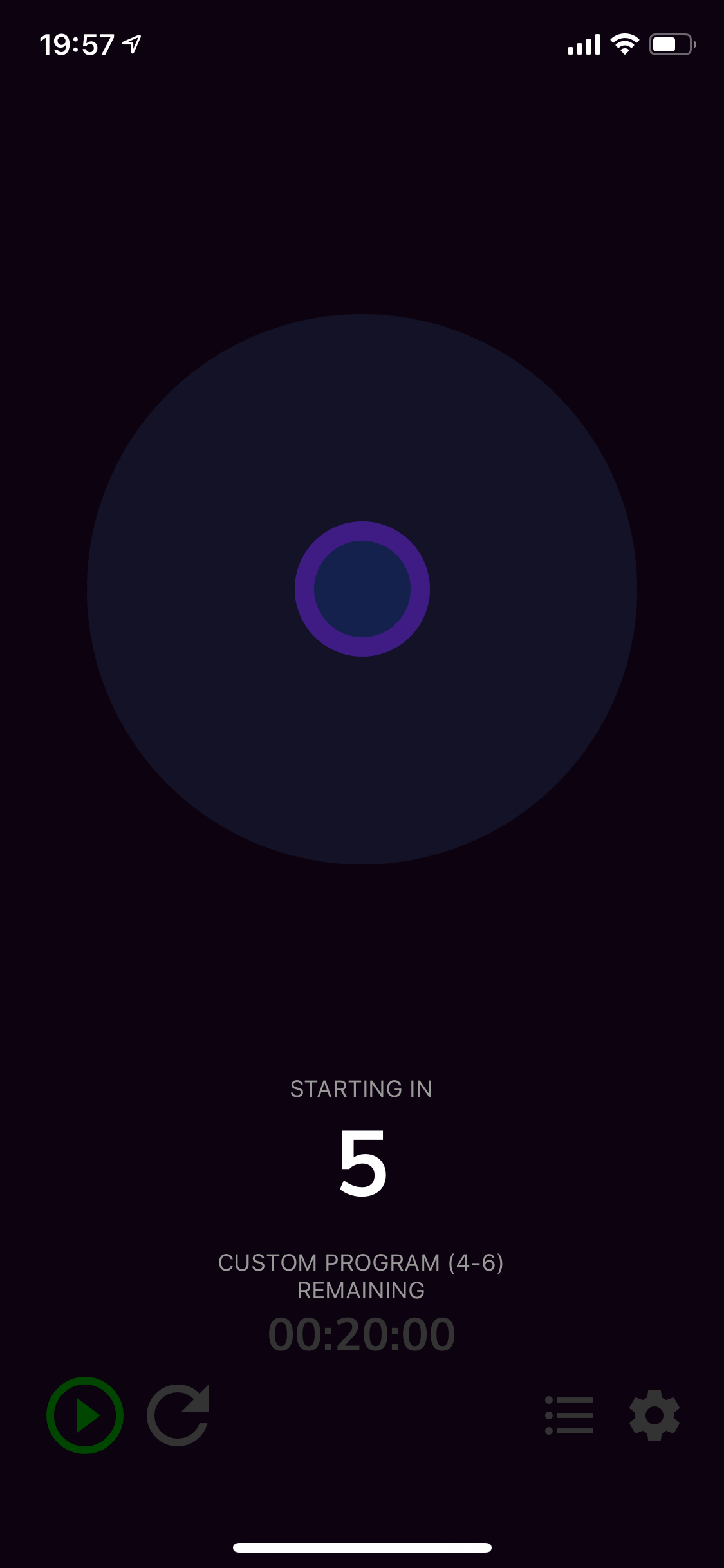

The minimum technology you need, whether you want to determine your resonance frequency or prefer to skip this step, is a breath pacing app.

Lagos recommends various apps, each with its unique look and feel, and suggests going for the one that is most pleasing to you.

After some experimentation with two or three apps, I settled for the extremely simple (and free) app Awesome Breathing: Pacer Timer.

The app allows for custom breathing patterns (down to 0.1-second precision) and features a simple but effective graphic of an expanding and shrinking circle.

Just like Lagos, I’d suggest taking some time to play with a bunch of apps and see what feels best for you. You will be spending a lot of time staring at this app if you decide to follow the program.

Once you’ve found your app of choice, it’s time to find your resonance frequency if you choose to do so.

For this, you need some extra gadgets. Basically, you need something that can fairly accurately measure your HRV in more or less real-time.

There are plenty of pieces of gear out there for this at various price points.

Personally, I was considering investing in some of the more specialized ones, particularly the CorSense by EliteHRV, but in the end settled on one I already owned: my Oura ring.

While the Oura ring is definitely not specifically designed for this purpose — its focus is on sleep tracking after all — its more recent Moment feature allows one to take reasonably accurate HRV snapshots during the day for intervals as low as five minutes. I’ll mention more about this (and some of its challenges) later.

Whatever device you choose to measure your HRV, now it’s time to determine your resonance frequency.

Measuring Your Resonance Frequency

The process is pretty simple. Set your breath pacer to five minutes (Lagos recommends two minutes in her book, but that wouldn’t work for me with the Oura ring), and then scan through a range of breathing frequencies, measuring your HRV for that time at each of these frequencies.

Besides HRV, Lagos also recommends noting down how natural/comfortable that frequency felt to you. If you want to go gadget-free, you can also try to estimate your resonance frequency purely by how comfortable it feels.

For me, the results looked like this:

3.7s inhale/5.5s exhale (6.5 breaths/min):

Not bad once I got into the rhythm

HRV: 64 ms; HR: 60 bpm

3.8s/5.8s (6.2 breaths/min):

Felt a bit too fast

HRV: 78; HR: 62

4s/6s (6 breaths/min):

Still a little bit fast

HRV: 75; HR: 61

4.2s/6.2s (5.7 breaths/min):

Still a bit fast

HRV: 64; HR: 60

4.4s/6.4s (5.5 breaths/min):

Seemed a bit better

HRV: 64; HR: 61

4.8s/7.2s (5 breaths/min):

Felt good

HRV: 57; HR: 62

According to this data, my HRV at that time seemed to naturally sit at around 64 ms, but to express a peak of 78 ms when breathing at around 6.2 breaths/min, with an inhale of 3.8 seconds and an exhale of 5.8 seconds. However, since slower frequencies seemed to feel a bit more natural (and I also wasn’t sure how trustworthy the Oura data was over only five minutes), I slightly nudged that up to 3.9s/5.9s (6.12 breaths/min).

Intention and awareness

In addition to a very data-focused approach, what maybe differentiates Lagos’s method most from “plain” resonance breathing, is that she couples the breathing with additional reflection practices and mental “reinforcement,” including concrete intentions and visualizations. For the full details of this, I highly recommend checking out her work directly, since it goes beyond the scope of this article. But I will at least mention some of these, as they are part of what makes each week of the program different.

To begin with, Lagos suggests becoming aware of one or a few goals for why you are engaging in this practice and remind yourself of these goals before every practice session.

Personally, I came up with three separate goals. Two of them were quite specific and personal, so I won’t go into them, but the third one read simply “Feel energized, positive and motivated throughout the day and then easily switch off at night.”

Now, with my resonance frequency determined (or at least guesstimated) and my goals set, it was time to begin the first week of the ten-week program.

Week 1

The program starts simple.

For the first week, you just sit down comfortably with good posture for 20 minutes twice a day and breathe at your resonance frequency using your breath pacing app, inhaling through your nose and exhaling through your mouth.

20 minutes twice a day, each and every single day, might sound like a lot. But Lagos really stresses the importance of this regularity in order to achieve the desired effect.

I was initially also slightly worried that I wouldn’t stick to it.

I’ve been meditating on and off for many years but was never really sure if it actually did anything for me and also, maybe as a result, found it hard to practice on a daily basis. Even as little as ten minutes once a day often just wouldn’t stick as a habit. And I never ever had practiced twice a day with any regularity.

But once I started this program I was pleasantly surprised that resonance breathing has definitely been the practice I found easiest to stick with, and from which I also perceived the most concrete effects.

I guess part of the reason is that for me, as a very data-driven person, HRV training in the form of resonance breathing has a very clear advantage over many other breathing or meditation techniques. The fact that I can measure and quantify it to some extent really helps me to stick to it on a more regular basis, and it boosts my belief in the efficacy of the technique, which probably further increases the positive effect it has.

To track progress over time, Lagos suggests measuring your HRV during weeks 1, 4, 7, and 10 of the program. During those weeks, measure on four separate days to calculate a weekly average. She clearly advises against tracking HRV on a daily or even weekly basis during training, since in many people this can have the opposite effect desired and just cause more anxiety.

I picked the mornings of Monday, Tuesday, Thursday, and Saturday for my measurements, used my Oura ring’s moment feature to determine my HRV (as well as HR) during these breathing sessions, and recorded them in my notebook (along with my nighttime averages and maxima, which I also got from Oura).

I will come back to these values in the conclusion and share some of my findings.

But that’s it for week one of the program. Two sessions of simple resonance breathing per day, 20 minutes each.

Week 2

Blood circulates through the body roughly once per minute, and much of the speed and strength of this circulation is actually due to the pressure that builds as we breathe. This pressure is largely driven by the diaphragm.

But as Nestor points out in Breath,

“A typical adult engages as little as 10 percent of the range of the diaphragm when breathing, which overburdens the heart, elevates blood pressure, and causes a rash of circulatory problems.”

Unfortunately, most of us are chest breathers instead of belly breathers, and our health — mental as well as physical — is suffering as a consequence.

“Most adults breathe absolutely the wrong way — from our chest, not our bellies. The fallout? Relentless stress, sluggish energy levels, emotional dysregulation, a worsening of chronic health conditions… Poor breathing technique impairs performance in essentially every area of life.”

— Leah Lagos

For week two, Lagos encourages us to reengage our diaphragm.

To do this, we slightly change the last five minutes of each breathing session to consciously practice belly breathing. Just put one hand on the stomach and one hand on the chest. Then make sure that while breathing, the hand on the stomach moves in and out while the one on the chest almost doesn’t move.

Personally, I realized during the belly breathing that my exhale felt a bit short, so I slightly adjusted my breathing pattern to 3.9 seconds inhale (as before) and 6.1 seconds exhale. This felt better and had the added benefit of giving me again exactly six breaths per minute, which kind of pleased my slightly OCD mind.

Week 3

When stressed, many people focus on their minds and try to address the issue there. But, as a growing body of research is showing, mind and body are much more intricately connected than we previously thought. To really fix the problem of stress and anxiety, we must start from the body.

Rather than completely blocking out any stressors or negative emotions, we want to allow ourselves to experience them, but then let them go.

“Week 3 is when you cultivate the ability to feel deeply and then set those feelings free.”

— Leah Lagos

To prepare for the exercise of week three, Lagos asks us to pick three stressors that come up in our daily lives on a regular basis.

Having identified these, we practice acknowledging and letting them go during the last five minutes of each breathing session (picking one stressor to focus on during each session).

More specifically, during each inhale we focus on one stressor, embrace it, and really become physically aware of how it feels. Then on the exhale, we let it go.

This teaches the body to experience the uncomfortable feelings but also to let go and release the tension.

One of the stressors I identified was the feeling of being a bit of a hypocrite. As I mentioned, I published a book about the importance of time off in 2020. But suddenly being considered an “expert” in time off also has its downsides (and I’d imagine the same to be true for any other expert).

Any time I didn’t completely live up to my own advice, when things got busy, I felt a strong sense of anxiety and imposter syndrome — very common among writers and “experts” of any kind. This was one of the feelings I focused on during the inhale and attempted to let go of with the exhale.

Interestingly, independently from my breathing practice, trying to really experience any stressful emotions, asking myself what they physically feel like, sitting with them for a while, and then letting them go, was also what my counselor recommended to me around the same time.

Lagos also notes that during week three or four, around 60% of her patients experience what she calls a “Heart Clearing.” She describes it as unexpected and sudden emotions like anger or tearing up, without knowing any explicit cause, and notes that it’s almost always a singular event, second ones being very rare. So if we experience one, we should fully lean into it and try to make it as deep and full as possible when it happens.

Personally, I did not experience this.

Lagos also directly works with patients. My guess is that it’s much more likely to experience something as strong as this when working with a professional rather than going the “self-guided” route. If I get the chance in the future, I would love to go through the program again with a professional. If nothing else, it just adds a much stronger level of accountability and commitment to the practice.

Week 4

While week three focused on simple stressors and the mind/body connection, week four takes this to a deeper level and looks at more of the lasting traumas, big or small, which each of us carry.

Often, trauma is more imprinted in the body than the mind and leads to unconscious triggers.

“It’s time to exorcise those repeating themes and thoughts that gnaw at your heart and mind, your ghosts.”

— Leah Lagos

To prepare for this week’s exercise, Lagos asks us to identify our “ghosts,” past experiences of lasting disappointment, anger, or frustration.

Some examples of the types of experiences mentioned in the book are:

“How did it feel when you couldn’t obtain your mother’s approval even when trying your best? How did your heart feel when you were teased by classmates?”

Again, rather than conjuring up a mental image, Lagos encourages us to focus on the physical sensation, especially how this memory feels in our hearts.

For week four, we repeat the exercise of week three but during the morning session focus on one of our ghosts during the inhale, and during the evening sessions focus on a particular stressor we experienced during the day (which might be triggered by one of the deep-seated ghosts, or hold clues to help us identify them).

Week 5

Week five stands under the theme “Preparing for Challenge,” and this week’s exercise, what Lagos calls a “Heart Shifting,” proved to be my favorite.

While I found it generally extremely useful, its main purpose is to prepare for an anticipated stressor (e.g. before an important meeting, a performance, or some unpleasant confrontation).

“Your heart knows how to feel stress and hold on to it. Now you are going to teach it how to feel that stress and automatically let it go.”

— Leah Lagos

For this exercise, the final breaths of each 20-minute session get split into three parts. Lagos suggests five breaths for each phase, but personally, I found it easier to go with one minute per phase.

Phase 1, “Clear the Heart”: As in the past two weeks, focus on the stressor during inhale, and let go during exhale.

Phase 2, “Clear the Mind”: Purely focus on the breath itself, like in some forms of mindfulness meditation.

Phase 3, “Shift the Heart”: Now, on the inhale focus on how you want to feel during peak performance. And during exhale let go of any lingering negative emotions or doubt.

This would comprise the last three minutes of each of my 20-minute breathing sessions.

Right after the very first session of doing this, I felt a strong sense of euphoria and energy, and I stood up with a huge grin on my face for no apparent reason. And this continued for the entire week.

Somehow for me, the shift from negative to positive seems to be much more effective than working on either side in isolation.

In the previous two weeks, I also struggled a little bit to really recall a memory or stressor in the short timeframe of an inhale, and then to disengage that thought again on the not much longer exhale.

One piece of advice that Lagos shared that week helped me get much better at this:

“Allow the body to feel the memory first. If your mind starts to take over and tries to conjure up memories of the experience that you have stored in your brain, remind yourself to gently refocus on the heart.”

Previously I had tried to come up with visuals of the situation. It would take me a while to get them, and then they would linger into the exhale. The advice to focus purely on physical sensations, especially in and around the heart, really helped me a lot.

Interlude on Oura and HRV

We’re halfway through the ten-week program, and I think this is a good point to dig a little bit deeper into Oura’s Moment feature, how I used it for HRV measurements, and share some of my really interesting findings.

As noted above, measuring HRV is not something that’s recommended on a per-session basis, but only on four days each of four weeks during the program.

During each of these sessions, I used Oura’s Moment feature in the “Body status” mode, started an open-ended session, and then switched to my breath pacer. Once the breathing session was over, I’d switch back to Oura and end the measurement.

When looking at the results, which include data for HRV, heart rate, and skin temperature, I noticed some pretty interesting and consistent patterns.

Let’s first look at heart rate.

This pattern is actually pretty boring. My heart rate tended to be consistently above my nighttime resting baseline, and stayed mostly stable during the session, with some small fluctuations up and down.

Next, let’s take a look at my skin temperature.

Here things start to get considerably more interesting.

Overall, I observed that my skin temperature seems to pretty consistently increase over the course of the session. Increased skin temperature is considered a sign of relaxation. So this is definitely pointing in a good direction.

But where it gets really interesting, is HRV.

The pattern I consistently observed was that my HRV started out at an average level, mid-way into the session took a dip, and then at the end of the session soared, often even going well above my previous night’s baseline, which normally should be my most rested state.

My guess for what causes this pattern is that at the beginning of the session I’m fairly focused on the breathing, but then mid-way through my mind starts wandering (something I often observed), leading to the dip in HRV. But then during the final part of the session, where each week I had a specific objective — like focusing on my stressors and letting go of them — I would not only get back to the initial impact but dramatically amplify it.

This, to me, was a really convincing argument that the training is having a very concrete effect and works as advertised.

Also, it clearly shows Oura’s value for this kind of practice, despite not being its intended use.

However, as I mentioned previously, despite my praise Oura is certainly not ideal for this purpose.

In all the cases, it takes a few minutes for Oura to start tracking the HRV (which further makes my resonance frequency estimates earlier a bit questionable). Worse, in some cases the measurement drops out completely, giving only very incomplete data and unreliable averages.

Still, despite this, I can’t recommend Oura highly enough, especially if you want to use a single device for multiple purposes.

And using my Oura ring also had some concrete advantages over using a more specialized device. Specifically, it allowed me to make a fair comparison between my session HRV and my nighttime HRV. But more on this later.

Week 6

Week six focuses entirely on positive emotions.

Lagos asks us to identify three very positive experiences, and in the last five minutes of the session focus on the physical sensations of these experiences during the inhale, and let go of any stress during the exhale.

For me, while my book indirectly caused some anxiety, it was also one of the most positive experiences in my life. Publishing the book, especially holding it in my hands for the first time, gave me a huge sense of accomplishment and possibility.

This feeling, or rather its physical manifestations, was one of the things I focused on while practicing in week six.

Interestingly, the exercise still felt good, but without first having the negative contrast, it didn’t seem quite as powerful as the “Heart Shifting” of week five.

Week 7

While the practice so far has been fairly detached from real life, week seven stands under the theme of “Cultivating Resonance Under Fire.”

To do this, Lagos encourages us to actually expose ourselves to one of our more mundane daily stressors during the session.

“Don’t choose a stressor that is overly upsetting such as a past trauma. This is not a clinical intervention, it’s an optimization strategy to target performance.”

She suggests picking the specific breathing exercise that resonated most with us (pun intended), and then to expose ourselves to a stressor for two minutes (or at least vividly imagine that stressor), followed by three minutes to use our technique of choice to address the stressor, ideally while continuing the exposure.

As you can probably guess I chose the exercise of week five. I identified a few stressors that I cycled through, but my most effective stressor of choice was imagining a totally packed Google calendar screen, with Slack notifications constantly popping up.

Week 8

Up until now, I had been fairly consistent in my practice. In the first four weeks I didn’t miss a single session and in the following weeks only a handful (all in the evening).

But from week eight, things went a bit downhill for me.

I live in Japan, but at the beginning of week eight, I traveled home to Germany for the Christmas holidays. The travel and ensuing jetlag, made worse by the fact that I was still working and had to get up extremely early by my standards to still have some overlap and meetings with my colleagues in Japan, made me miss (or rather skip), quite a lot of sessions, and the ones I did were of pretty low quality.

Add to that the stress of traveling during a pandemic, and the highly unrecommended diet consisting largely of Christmas cookies and beer, and my body was overall not particularly happy or rested. This was not only noticeable in my breathing sessions, but also in my sleep metrics. But more on the data in just a bit.

Under normal circumstances, week eight should have been focused on “Imprinting the Physiology of Success.”

The idea is to pre-meditate and visualize a success or achievement before it even happens.

First, you should think of a specific goal you want to achieve over the next month and write it down in as much detail as possible.

Then, try to switch off your outcome-focused mind and see what achieving this goal would make you feel like in your heart. Write down three emotions you’d experience. These are your imprints.

During the final five minutes of the breathing session, focus on these imprints.

“The breakthrough comes when you really click into understanding that you can train your heart to feel your future physiological state before you have even achieved your goal.”

— Leah Lagos

My high-level goal was to take some good time in solitude to write several high-quality articles that I’d be really proud of (one of which turned out to be the sleep tracking article I shared earlier).

Once we’ve identified our imprints, Lagos also recommends not only to use them during our 20-minute sessions, but also as a quick and effective tool during any stress or anxiety spikes we might experience throughout our days.

Week 9

Studies show that people with higher interoceptive ability, an ability to sense one’s own internal physiological signals, are also better at reading other people’s emotions.

Week nine aims to improve this interoceptive ability, and in turn our relationships, by trying to estimate our own heart rate. The book also outlines a partner exercise for this week, if you choose to practice with a partner.

Lagos points out that,

“Research confirms that people with higher HRV have sex more frequently. Not only that — it’s better sex.”

Well, that was definitely not the case for me in this particular week. Not only did I practice alone, but the timing for a week focused on connection and relationships was somewhat unfortunate since I was still completely self-quarantining after my arrival in Germany.

Nonetheless, I went ahead and tried to strengthen my interoceptive ability.

The exercise for the week, again performed at the end of each 20-minute session, was the following.

Set a 30-second timer and count your heartbeats without feeling the pulse. Double the number to get your heart rate. Then do the same but feel the pulse to cross-check.

Next, do some exercise for a few seconds to increase heart rate and repeat the procedure.

Finally, do two minutes of resonance breathing and at the end try to estimate your heart rate without a timer.

The goal is to become more and more accurate in your estimates, getting more and more in tune with your body.

Personally, I didn’t find it too difficult to count my heartbeats even without feeling my pulse, and it didn’t feel like this exercise did much for me. But I should also say that this week was kind of a low point due to the stressors around travel and Christmas already mentioned in week eight.

Week 10

Week ten introduces a final exercise called “The Bubble.” The goal is to be able to cultivate resonance even when faced with people or situations that tend to drain our energy.

The exercise unfolds in four steps.

Step 1: Visualize a bubble slowly wrapping around you, starting at your right foot, going all the way up to your right ear, and then down the left side to complete the bubble around you.

Step 2: Focus on your heart and the love and safety you feel in the bubble.

Step 3: On inhale, focus on the negativity in your body: stress, tension, anxiety… On exhale, push it out of your body and out of the bubble.

Step 4: Return to the feeling of love and safety.

I’m usually not that good at visualization exercises, but surprisingly, I really enjoyed the bubble.

Particularly the exhale part, where I imagined myself to be underwater, and my exhalation to form tiny bubbles that would rise up and away from me, felt very relaxing.

So for this final week, the last five minutes of each session are spent in the bubble.

And that’s it. Ten weeks of resonance breathing done. Was it worth it?

My Conclusion

According to Lagos, resonance breathing can have numerous and varied benefits, including:

- Less mind chatter and more control over your thoughts.

- Decreased stress and anxiety.

- Relieved medical conditions related to ANS dysfunction.

- Get better at connecting with positive emotions and trigger them.

- Increased stamina.

- Better emotional regulation and overall mood.

- More empathy.

And I was very impressed that the method lived up to the claims.

With the exception of “relieve of medical conditions” (I didn’t have any concrete condition I was trying to address) and “increased stamina” (I wasn’t really active during that time in a way that would have allowed for me to really notice or quantify this), I can say that I feel like I have personally perceived all of the promised benefits. And I think my counselor would agree with this.

One thing that I was initially expecting, but that didn’t happen, was an actual increase in HRV over the ten weeks.

Tracking both my nightly average values, as well as the values from the practice sessions in weeks 1, 4, 7, and 10, I got the following diagram.

Unfortunately, I see pretty much the opposite trend I had hoped for, with my HRV decreasing over time.

However, I don’t think this should be seen as purely negative and requires a bit of interpretation.

First of all, I’m very aware that this was a particularly stressful time, and I’m conscious of several stressors that became particularly pronounced during this time. So who knows how this graph would look like without the training.

Further, it’s impressive to see that in weeks four and ten my session HRV was actually higher than my HRV during sleep, which should usually be by far the most relaxed state.

Beyond this, I already showed my session HRV plots earlier, which indicate that maybe the average is not particularly high, but I was able to trigger a strong HRV peak in the final phase of each session.

Looking purely at the curve of the session HRV, it’s also worth noting that in week four, when my average session HRV peaked at above 80ms — a pretty impressive value outside of sleep — I was definitely the most committed to the practice. After week seven, as I noted above, I fell a bit off the wagon, getting more sloppy and less focused or even skipping sessions completely.

Interestingly, one thing that did seem to improve, was my respiratory rate during sleep.

I have Oura data on this reaching back several years, and my respiratory rate has always hovered fairly consistently in the range of 12.5 to 13 breaths per minute, never dropping below 12.25.

However, during the ten-week program, my respiratory rate quickly reached a new all-time low in week six of less than 12 breaths per minute.

Sure, this could be a random fluctuation, but I believe that it is quite likely that my 40 minutes of conscious slow breathing every day also decreased my breathing rate when I was not consciously focusing on it.

Slow breathing, like resonance breathing, increases the CO2 concentration in our blood, which has a calming and desensitizing effect on our chemoreceptors. These are our internal sensors that, when CO2 builds up, give us the sense that we are out of air.

The problem is that anxious people often have over-sensitive chemoreceptors, and the slightest increase in CO2 triggers panic. But it’s a vicious cycle.

As Nestor points out,

“They are anxious because they’re overbreathing, overbreathing because they’re anxious.”

I’ve personally noticed this when practicing Wim Hof breathing, which contains periods of extended breath holds. When I was more stressed and anxious, my breath-hold times were dramatically reduced compared to usual, probably as a result of more sensitive chemoreceptors.

So I was very happy to see that — at least when I practiced in a committed way — my breathing slowed down not just when I was willing it to, but also the rest of the day.

As the resonance breathing had promised, I really did manage to re-train my autonomic nervous system to some extent.

Overall, I’ve been feeling much better during and after the program.

And as indicated by the light green shading in the plots above, I have continued my practice.

Lagos suggests that to keep the cognitive benefits, most people feel like they need to keep the twice-daily practice for at least five days per week. Personally, I cut down a little bit, doing only a single session (in the morning) on six or so days per week.

So far it’s working well for me, and I’m still really enjoying each of my sessions.

It’s become a habit, nothing I have to talk myself into doing anymore (as was often the case with meditation, or other breathing techniques like the Wim Hof method).

For now, I’m planning to continue with resonance breathing, using it not just for stress relief, but also performance optimization.

“With a new and deep understanding of heart rate variability, you now possess a systematic, time-oriented, physiology-first approach for tapping into a performance oriented state. […] You’ve done something incredible: you have optimized your nervous system for peak performance.”

— Leah Lagos

And maybe one day I will revisit this more intense program, hopefully with a professional to guide me through the program and hold me accountable.

I hope you give it a try as well and find it as useful a tool in combatting stress and anxiety as I did.

Save 10% and get free shipping with a subscription!Fight viruses, remove heavy metals and microplastics, and restore your gut all at once with

Humic and Fulvic Acid from Ascent Nutrition.

MUST HAVE DETOX POWERHOUSE!

About The Author

Max Frenzel

AI Researcher, Writer, Digital Creative. Passionate about helping you build your rest ethic. Author of the international bestseller Time Off. www.maxfrenzel.com

Stillness in the Storm Editor: Why did we post this?

The news is important to all people because it is where we come to know new things about the world, which leads to the development of more life goals that lead to life wisdom. The news also serves as a social connection tool, as we tend to relate to those who know about and believe the things we do. With the power of an open truth-seeking mind in hand, the individual can grow wise and the collective can prosper.

– Justin

Not sure how to make sense of this? Want to learn how to discern like a pro? Read this essential guide to discernment, analysis of claims, and understanding the truth in a world of deception: 4 Key Steps of Discernment – Advanced Truth-Seeking Tools.

Stillness in the Storm Editor’s note: Did you find a spelling error or grammatical mistake? Send an email to [email protected], with the error and suggested correction, along with the headline and url. Do you think this article needs an update? Or do you just have some feedback? Send us an email at [email protected]. Thank you for reading.

Source:

Leave a Reply